PHELPS NY— Looking back on her life as a little girl living in a single-wide trailer in the town of Phelps, Laura Hinckley described her growing up years as shrouded in dysfunction.

Hinckley, now 51, called it a complicated existence for her family of 10 — one that was exacerbated by a hard-working but troubled mother who struggled with alcoholism.

Through the bouts of abuse they endured, Hinckley and her seven siblings forged a tight relationship. One of her big sisters, Sheryl Tillinghast, provided much of the familial warmth to the tepid atmosphere inside the crowded home.

Hinckley’s voice softens when she describes her big sister.

Tillinghast was a strong and mothering person who was devoted to making sure her siblings were taken care of, particularly the young ones like herself. Hinckley noted that Tillinghast and her mother, Gertrude Belcher, at times would butt heads about how she was treating the younger children.

“She would interact with us regularly and made sure we had something to do,” Hinckley recalled. “She would take us on picnics and she’d bake cookies for us on the holidays. She was the one who baby-sat us and took care of us. She was very nurturing.”

Those memories are all Hinckley has left of her beloved older sister, as more than 40 years ago — in September 1973 — a 17-year-old Tillinghast disappeared without a trace.

Space between

In January 1973, when she was 16 years old, Tillinghast departed for Dutchess County after running into legal trouble — she was found with a small quantity of marijuana, according to Hinckley.

Tillinghast ultimately was assigned to carry out community service work at Wassaic State School in the town of Amenia. The school, which opened in the 1930s, provided education and services for people who were developmentally delayed.

By June 1973, she was officially done with her sentence and released from her duties at the school, but she stayed on after she was hired to work in the facility’s laundry room.

The plan all along, according to discussions with her family, was that Tillinghast would come and visit her family soon.

“She had a great relationship with her sisters,” said New York State Police Investigator Thomas Crowley, of Troop E based in Canandaigua.

Crowley has been working on Tillinghast’s cold case since 2012.

“While she was gone, she would write a letter every other week to her sisters,” the investigator said. “She was concerned about them. She wanted to know that things were going well for them and that they were being taken care of, and she had concerns that maybe they weren’t.”

Tillinghast would never visit, however, and by September 1973, her letters to the house stopped as did her employment at the Wassaic State School.

Despite the tumultuous relationship between the two, Tillinghast’s mother, Gertrude Belcher, dug into her daughter’s mysterious absence, but did not get any answers.

Belcher was told by school officials and Tillinghast’s caseworker that the 17-year-old was an adult — if she wanted to come home she would, Hinckley said.

“My mother got it in her head that she just left,” she added.

For Hinckley, that statement doesn’t add up, and letters she found decades after Tillinghast’s disappearance proved her suspicions, she said.

Before she vanished, the now missing teenager sent letters to a judge requesting that a caseworker go to her former home and check up on her younger siblings.

“She was worried about our health and welfare,” said Hinckley, who was 9 years old when Tillinghast was last accounted for.

“I was about 36 years old when I saw those letters,” she said. “That made me 100 percent convinced that this was not somebody who just picked up and left.”

That Tillinghast was the victim of foul play was the only conclusion that made sense to Hinckley. Through years of uncovering layers of information about the disappearance, that theory has now become a certainty for Hinckley.

Starting to add up

“The first few years that she was gone, I just anticipated that my sister would come home at some point,” Hinckley said.

She remembers her mother saving wrapped birthday presents for Tillinghast, preparing for the possibility of her lost daughter walking through the door.

And as the years passed, along with birthdays and holidays, the family believed that law enforcement was actively searching for Tillinghast.

However, that was not the case.

“Everyone in the family had assumed that the older siblings had reported her missing,” Hinckley said. “But in 1998 we discovered that nobody had.”

By 1998 — around 25 years after the disappearance — Hinckley had given up hope that Tillinghast was alive, but she hoped there would be answers.

Already behind the eight ball, the case was taken on by the State Police, with investigators jumping into the case with countless searches, Crowley said.

“We’ve had investigators knock on doors in downstate New York in the areas where she used to live, and talked to people face to face,” Crowley said.

The conclusion among investigators leaned toward Hinckley’s beliefs.

“There’s just no indication that she ran away,” the investigator said.

Supporting the theory was the discovery that Tillinghast had left behind two paychecks and all her personal effects in her apartment located on the Wassaic State School property.

Also, there has been no use of her Social Security number through the decades.

But with no sign that she ran away, there’s also no sign that she’s alive.

Crowley said there are suspects, but for Hinckley there is a prime suspect — a man whom her sister became involved with romantically at the Wassaic State School.

He was an older man who had also worked in the laundry facility. His family members were administrators at the school, according to Hinckley.

During the early morning hours of Aug. 29, 1973, Tillinghast called police to have the man she was seeing arrested after he allegedly assaulted her.

After he was apprehended hours later by law enforcement, he was arraigned in court, but a relative promptly posted his bail.

In October 1973, a court appearance regarding the alleged assault was set up, but by then Tillinghast was already gone. The case fizzled out.

“We know that she had a boyfriend and we know that there was some trouble there,” Crowley said, referencing police reports that were reviewed and a general framework developed.

“We definitely have suspects, and that boyfriend is a suspect,” the investigator added.

Opening the past

While living in Missouri, Hinckley came in contact with an investigator from the Poughkeepsie area who had stumbled on her sister’s case a few years earlier.

In 2013, she made the decision to talk to the investigator face to face and see Wassaic State School, which is now closed.

Hinckley traveled the hundreds of miles north to upstate New York with her daughter by her side. She would stroll the grounds of the school that seemed haunted to her — she even snapped photos of the decrepit laundry facility where her sister worked. Inside, Hinckley walked the halls that her sister had most likely walked in.

While in the area, Hinckley attempted to reach out to people who had worked at the school as well as police officers from the area. Nobody remembered Tillinghast.

Hinckely wonders why school officials didn’t report her sister missing with all her belongings that were left behind — a question that seems impossible for anyone to provide a clear answer.

It is a harsh feeling that Hinckley can’t help but feel — that the sister that she cherished and has waited for was a just “throwaway” to so many people.

She reflected on the thought that her mother didn’t do enough to find her long lost daughter, but she finds no use in holding resentment to her mother, who died in 1996.

“I loved my mother,” Hinckley said. “I don’t feel resentment toward her. I know that based on her past — based on what happened to her growing up — she did the best she could. As parents that’s all we can do.”

She believes that Tillinghast’s remains are somewhere around that decaying school. It’s a rural area, she said, one with a swamp and pond.

“What was she going through her last few minutes before she died — did she suffer?” Hinckley asked. “I’ll never have closure to know that my sister is still out there. You want to know what happened. In order to put this to rest, you need to know what happened to your loved one. Even if the truth of what happened is painful, you still need to know.”

‘Anything it takes’

Hinckley has since left Ellington, Mo., recently moving more than 1,000 miles away to Sanford, Fla.

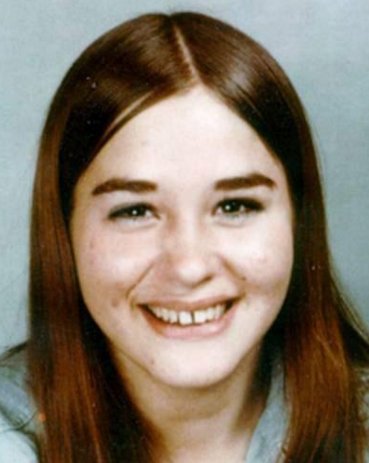

At her new home, she took some time to dig through some boxes to locate pictures of her lost sister. Those photos are intermixed with the four children of her own.

“She crosses my mind every day and I pray for her,” Hinckley said.

She noted that when her daughters turned 17, it was a cherished feeling that also magnified the pain she felt for Tillinghast, who would be 59 years old today.

“It makes me sad that her life was cut short at 17,” Hinckley said. “She didn’t get to do all the things that I got to do — get married, have children and watch them grow up, have grandchildren — to see the miracle of your family grow.”

The hope for Hinckley is that someday, somebody will come forward and provide the answers that she has prayed for for so long.

She sums up her dedication to finding those answers with ease — “Anything it takes,” she said.

“I can’t give up,” Hinckley said. “It’s not in me. I still hold out hope that there will be a miracle.”

— Anybody with information on this case is asked to contact the New York State Police, Troop E, Major Crimes Unit at 585-398-4100 or by email at nysvicap@troopers.ny.gov.