Be-a-Better Gardener

March 2018

A Fertilizer Primer

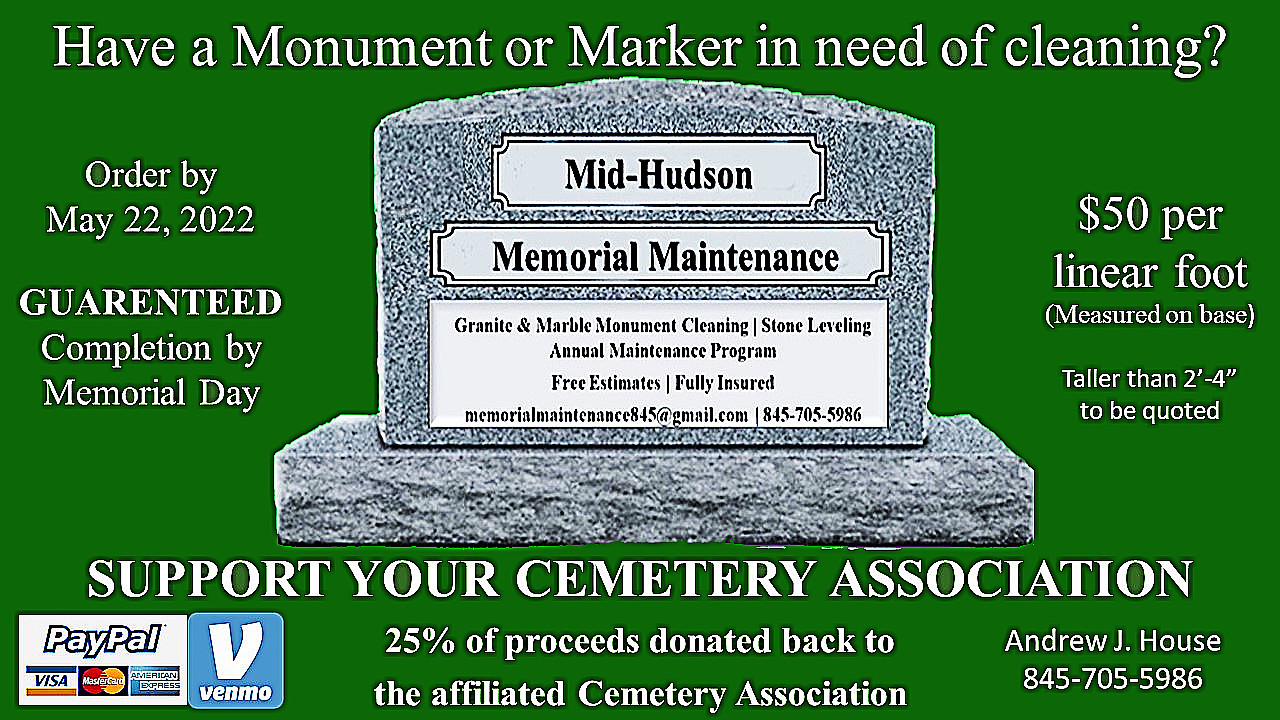

Testing your soil at the beginning of the growing season ensures that you will know what nutrients to add to your garden for optimum results.

By Thomas Christopher

Spring – which is breaking now, even in the North Country – is the season when gardeners start spreading fertilizers on everything from lawns to vegetable gardens. This can be a good thing or a very bad one, depending on the conditions in your garden, what you use, and how you apply it. So before you start, it’s a good idea to spend a little time understanding the materials and the process.

The first, and most important, rule is to test your soil before you fertilize. Take soil samples from the different areas you intend to treat and submit them to your state’s agricultural university soil testing lab for a basic nutrient analysis. The cost is modest, typically $10-$15 per sample, and you’ll probably save that much many times over because the test results will help you feed precisely, applying only the nutrients that your soil actually lacks. This greater precision also protects the environment – un-needed fertilizers are likely to wash into local streams or storm drains and either way contribute to water pollution. Excessive fertilization can also injure your plants, of course.

Armed with your soil test results, you’ll know what nutrients your garden or lawn lacks. Typically, the test results call for so many pounds of nutrients per 1,000 square feet. Translating this into pounds of fertilizer takes a little simple mathematics. On the fertilizer label, you’ll find a 3-digit formula, such as “5-10-5” or “26-5-10.” This formula tells you the fertilizer’s percentage by weight of the three major plant nutrients: nitrogen, phosphate, and potash. So, for example, a 5-10-5 fertilizer is 5 percent nitrogen, 10 percent phosphate, and 5 percent potash, which means that a 50-lb. bag of this product contains 2.5 lbs. of nitrogen, 5 lbs. of phosphate, and 2.5 lbs. of potash. Mastering this math can also save you money, as comparing the actual content of different products will help you determine which product delivers the most nutrients for the dollar.

Having done your math, you are set to go shopping. A second, and controversial, issue emerges at this point. Will you buy a fertilizer composed of natural or synthetic ingredients? Note that I didn’t use the term “organic” which as used in connection with fertilizers is intrinsically confusing. Scientifically speaking, organic refers to particular types of chemical compositions, which can be found in many unnatural compounds, and not in some natural ones. For instance, the insecticide DDT is, chemically speaking, organic, while granite dust, a common ingredient in “organic” fertilizers, is actually inorganic.

Natural fertilizers such as dehydrated manures or granular mixtures of different natural ingredients have both advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, because most of their ingredients must be digested by soil microorganisms to release their nutrients, they typically provide a slower, long-lasting feed. They also nurture the soil’s microorganisms, which helps keep your garden healthy. In addition, natural fertilizers generally add some small dose of organic material to the soil, which helps to enhance its structure and ability to absorb and obtain moisture. Their disadvantages include a lack of uniformity – depending on what the animal was eating, for example, a manure may be richer or poorer in nutrients. In particular, manures from feedlots, the source of much of the bagged manures for sale in garden centers, can be high in salts that are harmful to plants.

For these reasons I occasionally prefer to use a synthetic fertilizer. When feeding annuals in springtime, for example, I will use a synthetic fertilizer. Because the microorganisms are relatively inactive in cold soils, an organic fertilizer would not feed the plants until the soil warmed at spring’s end. In addition, if I notice a plant lagging, I may apply a synthetic fertilizer because they are faster acting.

Overall, though, I prefer to use natural fertilizers, in particular, those such as aged horse manure (.7-.3-.6, on average) that I can obtain by the pickup load without cost from nearby stables. I also favor compost (0.5-0.27-0.81, on average), which my wife makes in quantity because although it is very low in nutrients, it is rich in the kind of organic matter whose benefits to the soil I already explained. For a long time, my standby was the many bags of coffee grounds (2.1-0.3-0.3) that my wife scavenged from a busy local café. Because it was ground fine, this material quickly decomposed, adding nutrients as well as humus, in a couple of years turning what had been a heavy clay into a rich loam.

Thomas Christopher is the co-author of “Garden Revolution” (Timber Press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org

Be-a-Better-Gardener is a community service of Berkshire Botanical Garden, one of the nation’s oldest botanical gardens in Stockbridge, MA. Its mission to provide knowledge of gardening and the environment through 25 display gardens and a diverse range of classes informs and inspires thousands of students and visitors on horticultural topics every year. Thomas Christopher is the co-author of Garden Revolution (Timber press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org.

Robin Parow

Director of Marketing Communications

Direct dial: 413 320-4795