How a Financial Crisis Led to the Sale of 272 Enslaved People to Save a College—and the Ongoing Efforts to Remember Them

In the heart of Washington, D.C., Georgetown University stands as one of the oldest and most prestigious institutions in the United States. Yet buried within its walls is a painful history—one that traces back to June 19, 1838, when the Jesuits of Maryland sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children to raise money for the struggling college. This sale, known today as the Georgetown Jesuit Slave Sale, has left an indelible mark that the university continues to reckon with nearly two centuries later.

Jesuit Plantations and the Foundation of Georgetown

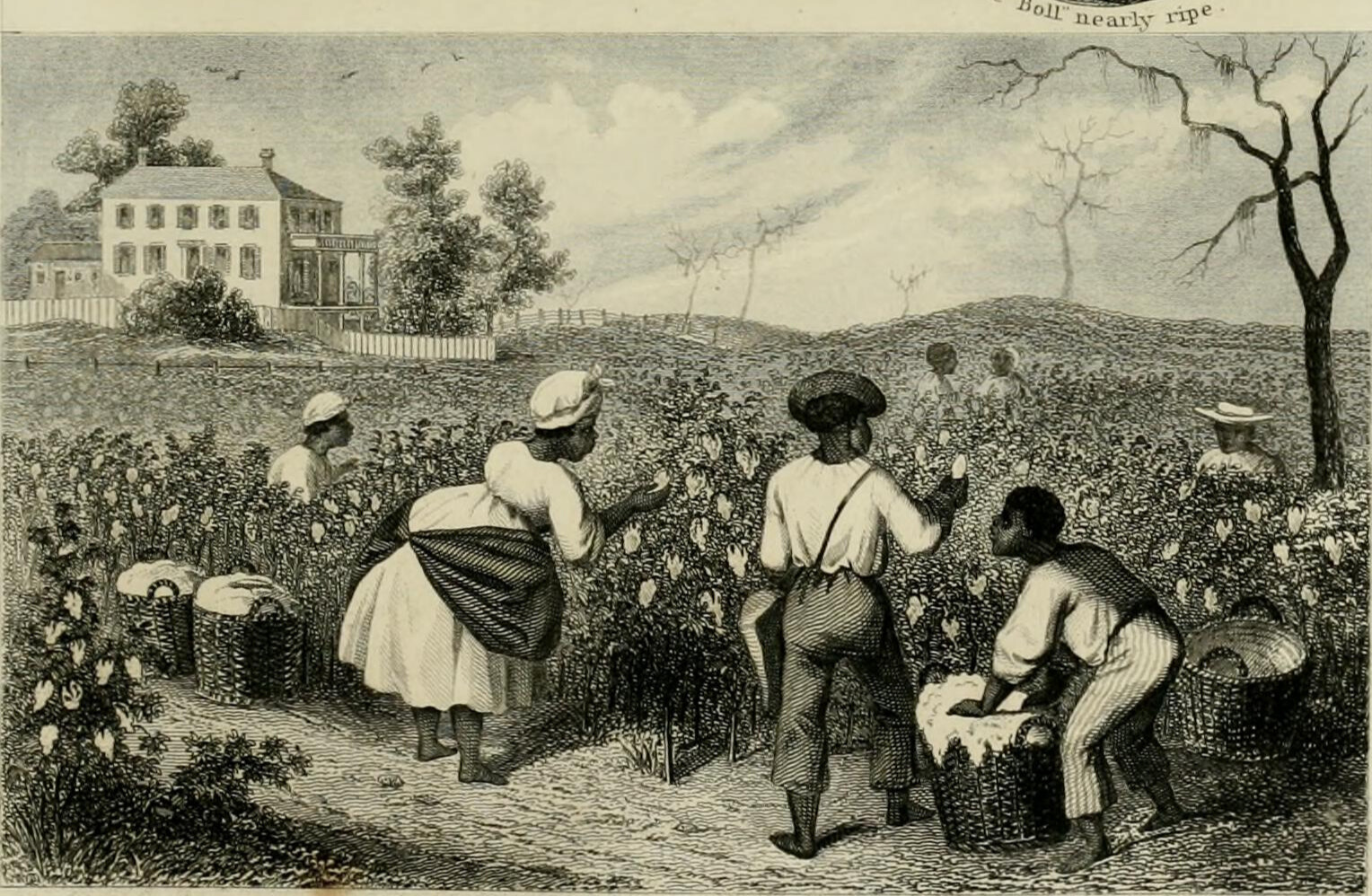

The Society of Jesus, commonly known as the Jesuits, began settling in Maryland in the 1600s, fleeing religious persecution in England. To support their religious mission and educational efforts, they operated large plantations that grew tobacco and corn, worked entirely by enslaved labor.

By the 1830s, the Jesuits owned six plantations covering 12,000 acres, relying on hundreds of enslaved people to generate income. Georgetown College, founded in 1789, was one of the institutions supported by this system. However, by the early 1830s, the college faced a severe financial crisis. To save it from bankruptcy, the Jesuits made the devastating decision to sell human beings.

Father Mulledy and the Decision to Sell

Father Thomas Mulledy, a former Georgetown College president and head of the Maryland Jesuits, played a leading role in orchestrating the sale. Alongside Father William McSherry, he proposed selling both land and enslaved individuals to relieve mounting debts.

In 1836, they requested permission from Jan Roothaan, the Jesuit superior in Rome. Roothaan agreed, but under three moral conditions: families must remain together, enslaved individuals must be able to practice their Catholic faith, and the profits should only support educational missions.

Despite these conditions, the resulting sale failed to honor these promises.

The 1838 Sale: Treating People as Property

On June 19, 1838, Mulledy signed a contract with Henry Johnson, a former Louisiana governor and U.S. senator, and Jesse Batey, a plantation owner. The agreement sold 272 enslaved people for $115,000, equal to over $3 million today. Johnson and Batey intended to use them on their sugar plantations in Louisiana.

The deal included payments over ten years with 6% interest. The first group of 51 people was transferred after a $25,000 down payment. Every person—men, women, children, and infants—was listed by name, their humanity reduced to line items in a contract.

More than half of those sold were under 20, and nearly a third were under 10. Many were forcibly separated from their families, directly violating Roothaan’s condition to keep families together.

The Voyage South and Life on Plantations

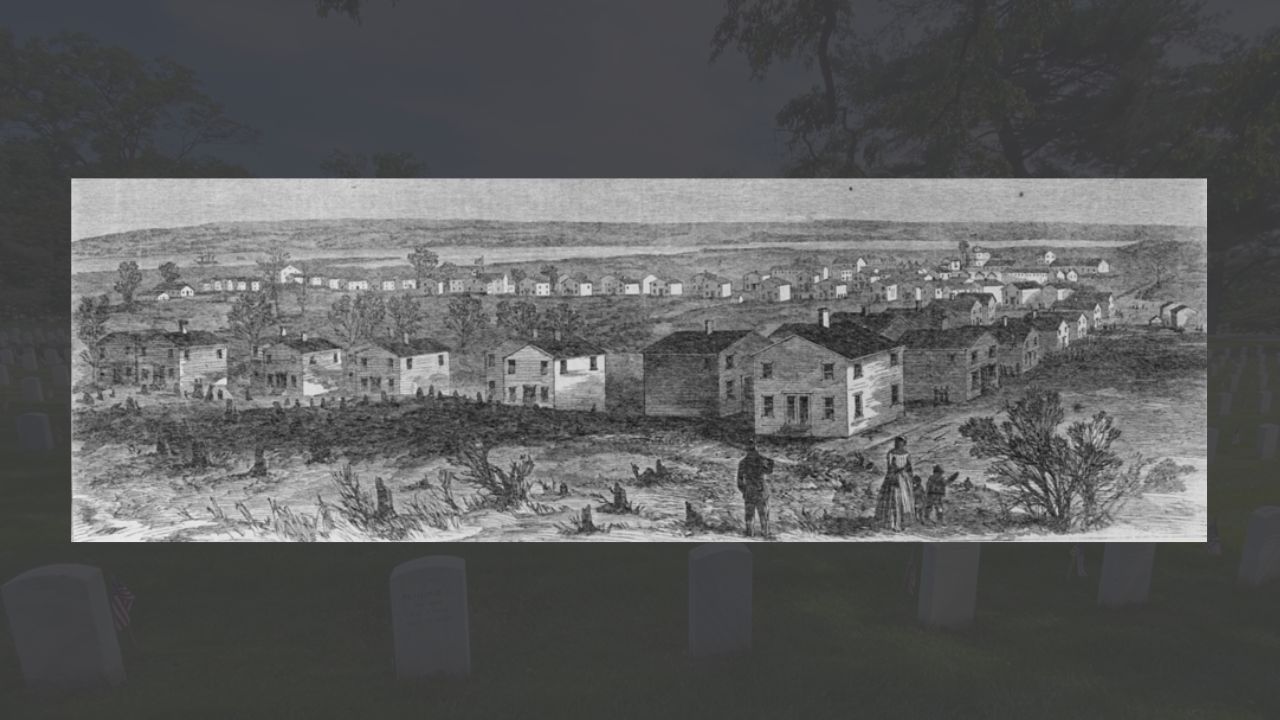

In November 1838, many of the enslaved were transported aboard the Katherine Jackson, a slave ship departing Alexandria, Virginia, for New Orleans. After three weeks at sea, the survivors arrived in Louisiana and were sent to plantations in Iberville Parish, including the West Oak Plantation.

Only 206 of the 272 enslaved people listed actually arrived in Louisiana. The others were either left behind, escaped, or died. Conditions on the voyage and on the plantations were harsh, with grueling labor and no rights.

Resistance and Reckoning

Not all Jesuits agreed with the sale. Priests like Father Joseph Carbery protested the decision and even warned enslaved families of their fate, helping some escape, including members of the Mahoney family. Roothaan later expressed deep regret, saying it would have been better to lose money than to commit such a moral wrong. He removed Mulledy from his position and sent him to France in punishment.

Georgetown College received $17,000 from the sale—almost half of its debt at the time. While it never received the full $115,000, the transaction undeniably stabilized the school’s finances, built in part on human suffering.

Rediscovery and Modern Accountability

The history of the 1838 sale faded from public memory until 2014, when student Matthew Quallen began investigating Georgetown’s ties to slavery in articles for the student paper, The Hoya. His work, followed by a 2015 New York Times investigation, forced the university to confront its past.

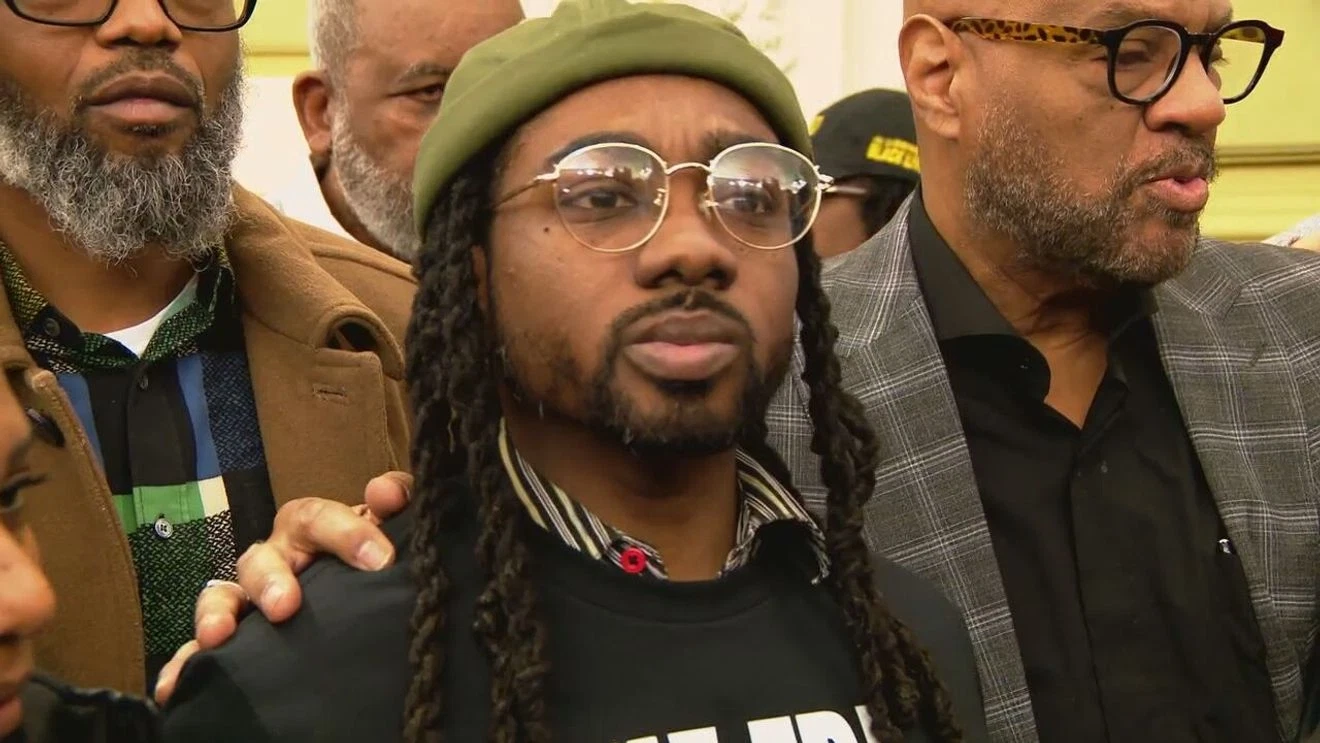

That same year, alumnus Richard Cellini founded the Georgetown Memory Project, which aimed to trace the descendants of the 272 enslaved people. Through archival research, DNA analysis, and old plantation records, the project identified thousands of living descendants, many still in Louisiana. These efforts led to the formation of the GU272 Descendants Association, named after the original 272 individuals listed in the sale.

Memorials and Ongoing Reflection

In 2017, Georgetown University renamed Mulledy Hall to Isaac Hawkins Hall, after the first person listed in the sale documents. A plaque outside the residence hall now honors the enslaved individuals whose lives were traded for the college’s survival.

Nearby, the Georgetown Slavery Archive in Lauinger Library offers public access to documents, records, and exhibits related to the sale and the university’s deep connections to slavery.

Conclusion

The 1838 Jesuit slave sale stands as a painful reminder of how educational institutions in America were often built on the backs of enslaved people. Though Georgetown University has taken steps to acknowledge its history—through memorials, scholarships, and partnerships with descendants—the trauma of the past still lingers.

This story is no longer buried. It is part of Georgetown’s legacy—a legacy the university continues to reckon with, and one the nation must not forget.

Leave a Reply