How a Washington, D.C. dance party became a nationwide movement of identity, health, and solidarity

Juneteenth is a day for liberation stories, and few tales illustrate that spirit better than the birth of Black Pride. Its roots reach back to the mid-1970s, when members of D.C.’s Black LGBTQ+ community opened a nightclub called ClubHouse. Each Memorial Day weekend the club threw a marathon dance bash known as “The Children’s Hour.” People traveled from every corner of the country for the music, the fashion, and a rare sense of belonging.

From ClubHouse to the First Black Pride

When ClubHouse closed in 1990, three longtime attendees—Welmore Cook, Theodore Kirkland, and Ernest Hopkins—refused to let the community’s annual homecoming die. They organized the nation’s first Black Pride celebration in May 1991, right in Washington, D.C. Their goal was simple yet revolutionary: create a space where Black LGBTQ+ people could celebrate themselves without apology or exclusion. The idea spread quickly; today nearly every major U.S. city hosts its own Black Pride weekend.

“Racism with a Glitter Lip Is Still Racism”

The expansion was fueled not only by joy but by necessity. In Rochester, New York, artist-activist Gatekeeper Adrian helped launch Rochester Black Pride after experiencing discrimination inside mainstream LGBTQ+ spaces.

“Racism with a glitter lip is still racism,” Adrian quips. “Painting it pretty doesn’t make it easier.”

Their words echo the experience of many Black queer people who, even within LGBTQ+ circles, still confront bias based on race, gender expression, or socioeconomic status.

Health Advocacy at the Core

The original Children’s Hour did more than fill a dance floor—it sounded the alarm about the emerging AIDS epidemic. That legacy endures. Modern Black Pride organizations still run on-site HIV testing, mental-health workshops, and panels on issues affecting the most marginalized members of their own marginalized community—trans people, youth, and elders alike. Black Pride is thus celebration and clinic, dance floor and safety net.

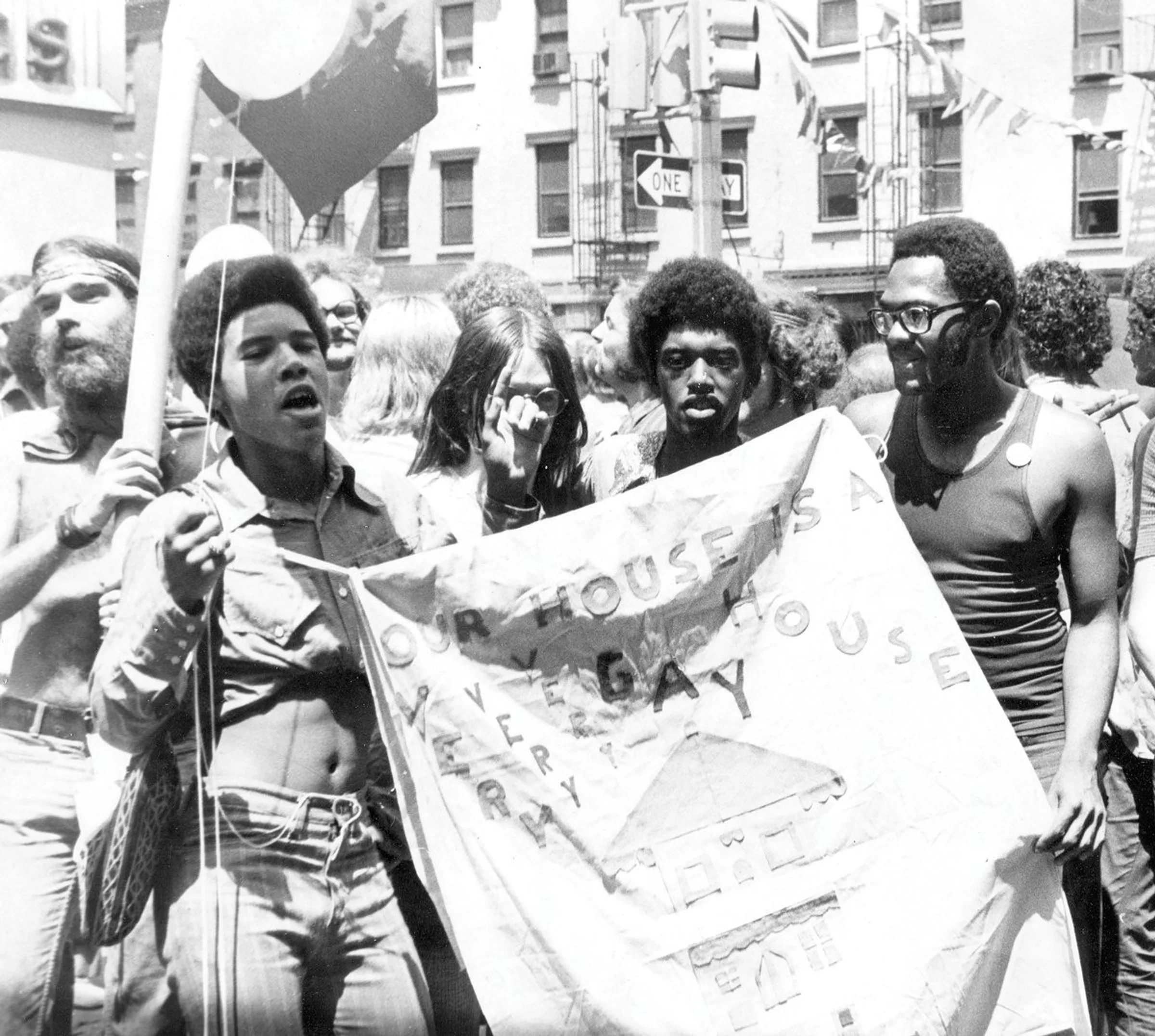

Moments in the Movement

-

Anti-War March, 1973: Black LGBTQ+ activists marched on Constitution Avenue, linking the fight against racism, homophobia, and militarism.

-

Inner City AIDS Pride, 1991: Activists rallied behind banners demanding care and research in the epidemic’s darkest days.

-

Capital Pride, 2017: Protesters chanting “No Justice, No Pride” halted D.C.’s parade, insisting that corporate sponsorship could not override racial and social justice.

-

Capital Pride, 2021: Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Douglas Emhoff became the highest-ranking U.S. officials ever to march in a Pride parade.

-

Upstate Black Pride, South Carolina: Live bands, spoken-word poets, and food vendors turn the summer heat into a festival of music and resilience.

Why It Matters—Especially on Juneteenth

Juneteenth commemorates the final enforcement of emancipation on June 19, 1865, when Union troops freed the last enslaved Texans. Black Pride commemorates a different kind of liberation: freedom to exist, love, and lead—openly and Black. Both observances insist on an honest reckoning with delayed justice while highlighting the power of community action.

On this Juneteenth we honor the twin progress of Black freedom and queer visibility. From ClubHouse’s strobe-lit dance floor to community health tents nationwide, Black Pride proves that liberation is not a one-time event; it is a practice—rooted in resilience and growing in unity.

Leave a Reply