Frederick Douglass’s name is etched in American history as a symbol of resistance, eloquence, and unrelenting pursuit of freedom. From escaping slavery in 1838 to becoming one of the most influential voices for civil rights in the 19th century, Douglass lived a life that defied the boundaries of race, class, and law. Perhaps no moment encapsulates this better than when, in 1877, he shattered Washington D.C.’s whites-only property restrictions by purchasing Cedar Hill — a powerful personal and political statement. That same year, he became the first Black U.S. Marshal, a federal appointment that required Senate approval.

Here is the extraordinary story of a man who went from slavery to Cedar Hill, from fugitive to federal official.

A Risky Escape Funded by Love

Frederick Douglass, born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, was enslaved in Maryland. His escape was only made possible by the unwavering support of Anna Murray, a free Black woman who would later become his wife. Anna used her entire life savings—earned through nine years of domestic labor—to finance Douglass’s escape.

She even sold her cherished featherbed and sewed him sailor clothing as a disguise. Using borrowed identification papers from a free Black sailor, Douglass boarded a train on September 3, 1838, and began his daring journey to freedom. When a conductor questioned him, Douglass confidently pointed to the American eagle on the papers and evaded suspicion.

Just 11 days after his escape, Douglass and Anna married in New York City. Their love would be a cornerstone of Douglass’s personal and political journey.

New Life, New Name: The Douglass Legacy Begins

Settling in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the couple adopted the name “Douglass” from a character in Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake. Frederick worked as a laborer, while Anna supported their growing family by taking in laundry.

Their son, Lewis Henry Douglass, would later serve as sergeant major in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War—one of the first official African American units in the U.S. Army.

From Orator to National Symbol

Douglass’s oratory skills were undeniable. His powerful speech at an 1841 antislavery meeting caught the attention of William Lloyd Garrison, who hired him as a speaker for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.

As Douglass traveled the country giving speeches, Anna held down the fort—often literally. Their Rochester, NY home became a key stop on the Underground Railroad, helping enslaved people reach freedom in Canada. Anna managed the home, hosted guests, and raised their children during his frequent absences.

Tragedy, Arson, and a New Chapter in Washington, D.C.

In 1860, their youngest daughter Annie died at age 10. The emotional toll was compounded in 1872 when a fire—believed to be arson—destroyed their Rochester home, including Douglass’s library and personal papers. This prompted a move to Washington, D.C., where Douglass would begin a new chapter as a national leader and public servant.

Breaking the Color Line: The First Black U.S. Marshal

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Douglass as U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia, making him the first African American to hold a federal position requiring Senate confirmation.

Although his role was largely ceremonial—he wasn’t invited to introduce foreign dignitaries like previous marshals—his very presence in the position shattered a racial barrier in the federal government.

Defying Discrimination: The Cedar Hill Purchase

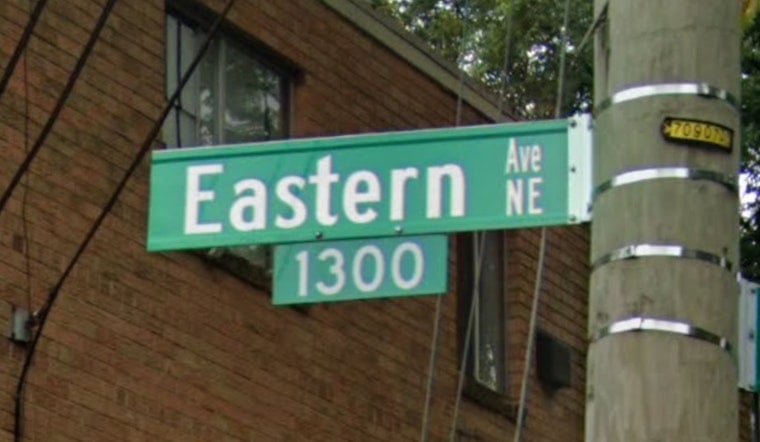

That same year, Douglass made a bold move by purchasing Cedar Hill, a 9.5-acre estate in Anacostia, a neighborhood where Black property ownership was prohibited by law. He paid $6,700 (equivalent to about $1.3 million today), effectively breaking the city’s whites-only housing rules.

Douglass expanded the property to 21 rooms, added stables, a water tank, guest quarters, and even a croquet lawn. He lived at Cedar Hill until his death and used it as a retreat, a political hub, and a symbol of self-made success.

Cedar Hill: A Home of Strength and Serenity

Douglass wasn’t just a political force—he was also physically strong. Into his 60s, he lifted weights on the front lawn, played croquet with friends, and tended to a “gentleman’s farm” with chickens, fruit trees, and a vegetable garden.

Visitors included key civil rights figures of the era, and the house overlooked the Capitol dome—a fitting view for a man who once had no rights at all.

A Legacy Cemented in Stone and Service

Frederick Douglass held five federal appointments across multiple administrations, including:

-

U.S. Marshal for D.C. (1877–1881)

-

Recorder of Deeds (1881–1886)

-

Minister to Haiti (1889–1891)

In 1884, after the death of his beloved wife Anna, he remarried to Helen Pitts, a white activist 20 years his junior. Their interracial union was controversial, but Douglass remained undeterred by public opinion.

On February 20, 1895, hours after being honored at a women’s rights convention, Douglass collapsed at Cedar Hill and died of a heart attack. He was 77 years old.

Today: The Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

Cedar Hill remains preserved as the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site at 1411 W Street SE in Anacostia. Visitors can:

-

Tour his original library, desk, and belongings.

-

Explore the reconstructed “Growlery,” where he wrote much of his life’s work.

-

See the lawn where he once exercised and played with family.

-

Learn about his advocacy, from slavery abolition to women’s rights and foreign diplomacy.

Tours are ranger-guided, and while admission is free, a $1 reservation fee is required. Hours vary by season.

Final Thoughts

Frederick Douglass’s life is more than a tale of escape from slavery—it’s the American dream fully realized. He defied racist laws to buy a home in the nation’s capital, became the first Black U.S. Marshal, and served as a trusted diplomat.

Cedar Hill isn’t just a house—it’s a monument to resilience, brilliance, and the belief that one person can indeed reshape the course of a nation.

Leave a Reply