When Martina learned last September that her landlord had filed an eviction case against her, she assumed it was a mistake—or a scam.

“How can you be evicted from a place that doesn’t exist?” she asks.

A Home That’s Gone but a Debt That Remains

Martina had lived in a two-bedroom unit at 4386 7th St. SE in Washington Highlands from 2020 to 2022. She and her family were temporarily relocated during the demolition of Belmont Crossing Apartments, with a promise that they could return to a new development, Barnaby & 7th, once construction was complete.

But in court filings, Belmont Crossing claimed Martina owed nearly $30,000 in unpaid rent between mid-2022 and mid-2024—long after her old building was torn down. The landlord won a default judgment after Martina missed a hearing, and in January, a judge issued a writ of execution for an eviction from an address that no longer exists.

The eviction notice was returned as undeliverable, prompting a magistrate judge to cancel the April eviction. Later, Judge Stephan Rickard ordered the landlord to justify why the case shouldn’t be dismissed. The landlord’s attorney admitted the goal was to prevent Martina from exercising her right to return to the redeveloped building. In July, Rickard dismissed the case.

A Promise to Return

Before relocation, Belmont Crossing’s website pledged a “Right-to-Return” policy and stable rents for former tenants. Those commitments were tied to agreements in which tenants waived their rights under the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in exchange for guaranteed access to the new units.

Yet Martina says no one from management has contacted her about returning. “My phone number hasn’t changed. My email hasn’t changed,” she says.

Legal Loopholes and Widespread Impact

Belmont Crossing’s attorney, Mark Raddatz, has filed more than 20 similar eviction cases against relocated tenants. Many are unrepresented in court, leaving them to navigate a confusing legal process. Some have been ordered to pay rent into court registries for apartments that no longer exist—amounts ranging from $725 to $1,025 per month.

In one case, a tenant mistakenly believed those payments covered her current apartment rent. Raddatz, in a hearing, refused to offer a payment plan, saying his client wanted a quick resolution.

A Celebration for Some, Uncertainty for Others

In June, city leaders and developers celebrated the ribbon-cutting for the first phase of Barnaby & 7th—the Uplands, a 169-unit building. Officials praised it as a model for affordable housing preservation.

But internal documents paint a different picture. A spreadsheet, accidentally shared with a former tenant, listed nearly 45 relocated residents on an “eviction suit list.” It included personal data like income, disability status, and rent subsidies.

For those tenants, proposed rents in the new building would be about 44% below market rate, making them significantly cheaper than units for non-returning residents. The document also indicated some tenants had been told they couldn’t return due to outstanding balances.

Life in Temporary Housing

Nicole, another relocated tenant, now lives with her husband and five children in a three-bedroom unit in Kingman Park. She says her temporary housing—promised to be “safe and sanitary”—is infested with rodents, plagued by roaches, and located in an area with regular gunfire.

By late 2024, Nicole begged Barnaby & 7th management to move her family, even asking if she could break her lease without penalty. Initially, Belmont covered the $820 rent difference between her temporary unit and her original rent of $1,395. But in May 2025, she was told those payments would stop.

“They never told us that they were going to stop paying before we move back,” she says. She borrowed money from work to pay June’s rent—then received an eviction notice for her demolished Belmont Crossing unit.

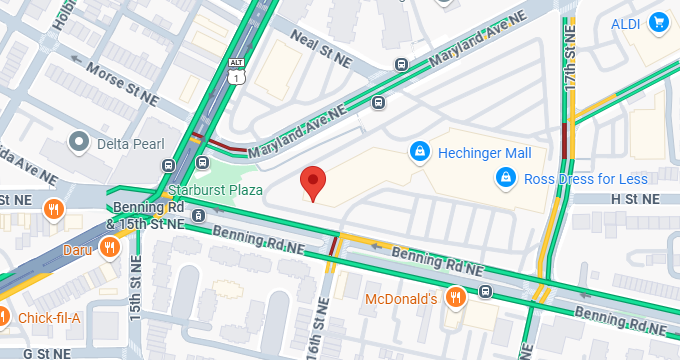

The Hawaii Avenue Cases

Belmont tenants aren’t alone. At 1 Hawaii Avenue NE, another affordable housing provider, Wesley Hawaii LLC—also represented by Raddatz—has filed at least seven similar eviction cases against relocated tenants. The old building has been demolished, and a new one is under construction.

Officials have touted the redevelopment as a success under TOPA, guaranteeing return rights for tenants “in good standing.” But in court, Wesley’s attorney admitted some cases were filed specifically to terminate tenants’ right to return.

In one instance, a tenant sued for $1,153 in unpaid rent presented receipts proving payment. Wesley quickly dropped the case, blaming a “miscommunication” among staff.

Legal and Policy Concerns

Legal Aid DC attorney Brian Rohal argues these cases stretch eviction laws beyond their intent. “Put simply, there can be no suit for eviction if there is no place from which to evict the defendant,” he wrote in one filing.

A new D.C. Courts Civil Legal Regulatory Reform Task Force report highlights the overwhelming number of unrepresented tenants in eviction cases, underscoring the need for more legal aid access.

Tenants in Limbo

For Nicole, the uncertainty is overwhelming. Belmont’s decision to stop covering her rent has left her on the brink of losing her temporary home. Without legal help, she fears she’ll be evicted twice—once from a building that’s gone and once from the unsafe apartment where she’s now living.

“It’s not affordable,” she says. “We try to pay for something that we can’t afford in a neighborhood that is not worth it.”

Still, she clings to the hope of moving into a safe, new apartment at Barnaby & 7th.

“A lot of tenants wanted to come back to something new and fresh, and to start all over,” she says. “A nice new beginning.”

Leave a Reply