No bad bugs

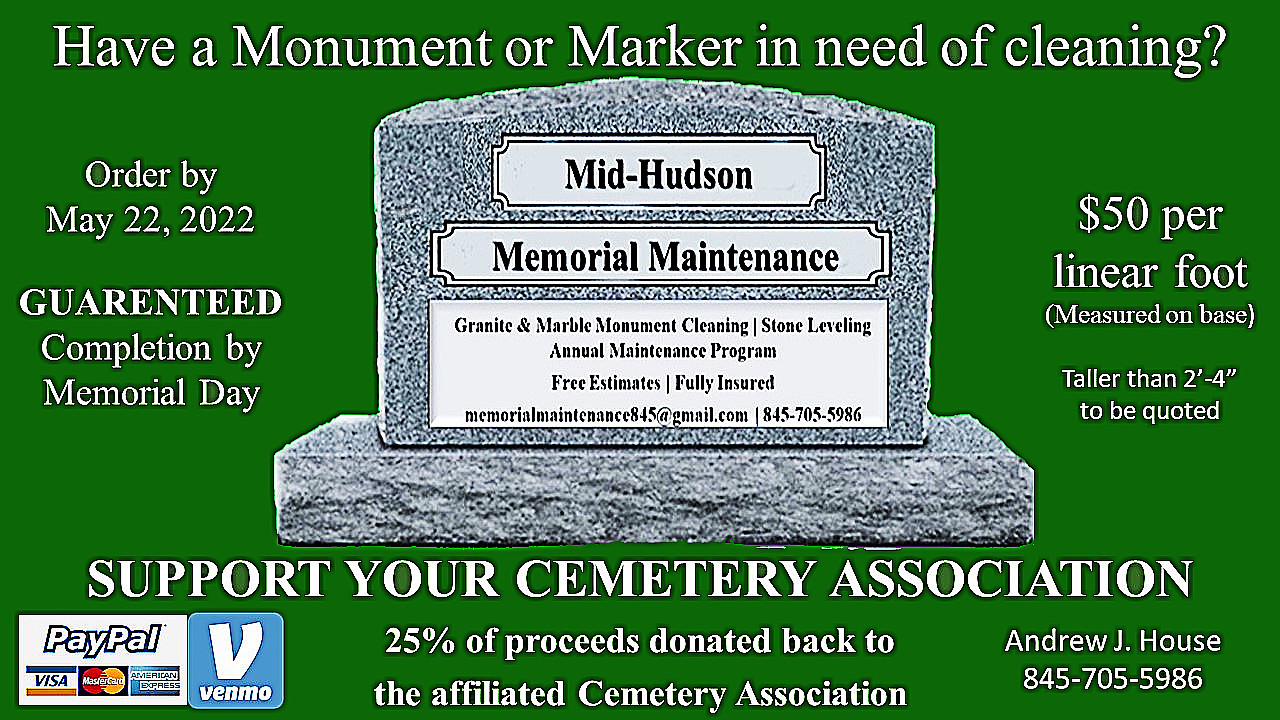

Ladybugs have a reputation of being “good bugs,” but when viewed through a close-up lens, all bugs look pretty good.

By Thomas Christopher

I’ve been thinking about my neighbor, Brian Stewart, a lot recently.

I came of age as a gardener at a time when any insect in the garden was regarded with suspicion. We labeled them indiscriminately as “bugs” as if they were just glitches in our otherwise perfect landscapes, something to be eradicated as thoroughly and quickly as possible. There were a few exceptions. There were the “good” bugs such as ladybugs and praying mantises, predators that assisted us in our crusade to slaughter the plant-eating insects, the “bad” bugs.

Things changed dramatically with the publication of Douglas Tallamy’s book, Bringing Nature Home in 2007. Tallamy, an ecologist at the University of Delaware, presented irrefutable evidence that plant-eating insects play a crucial role in the ecology of our landscapes. If we want our gardens to be hospitable to birds, in particular, we have to tolerate their food source, herbivorous insects. Indeed, with biodiversity on the decline throughout North America, cultivating native plants that in turn support rich and diverse insect populations is a duty of the enlightened gardener.

I think, however, that at this point we need to take a step even further. Which brings me back to Brian.

Brian is a scientist, a professor at Wesleyan University. In his spare time, he is, among other things, a keen gardener. He’s also an admirer of wildlife. He enjoys the birds that flit through his ¼-acre yard, and the various mammals that wander in from an adjacent nature preserve. But a decade ago, he began exploring close-up. After participating in a local “Bioblitz,” a crash program of assessing the local biodiversity, he decided to make a collection of local insects. Instead of killing the insects and pinning them to boards, however, he chose to take photographic portraits of what he found. He started in his own yard, thinking that he could broaden his search when he had exhausted its supply. Ten years on, he has never stirred beyond the boundaries of his own property. He has taken some 10,000 photographs of roughly 500 different insects, and he is still finding species unfamiliar to him right outside his front door.

Unlike most insect collectors, Brian doesn’t harm any of his finds. The most he ever does is to slip them into a container and chill them in the refrigerator for an hour or so, to numb the insects so that they will hold still for their portraits. After photographing them, he returns them all to the wild.

What Brian has discovered with his macro lens is a bizarre and beautiful world, one that is all around us but which we typically overlook. His portraits exhibit brilliant colors and metallic sheens, with strange, often extravagant structures. My favorites are his shots of the female giant ichneumon wasp. An anorexic black and yellow creature, this stingless wasp trails from its rear end a long ovipositor, a sort of tubular drill which it inserts into tree trunks or stumps to inject an egg into insect larva burrowing in the wood. If Dr. Seuss had turned to science fiction, this, I believe, is what he would have created.

Identifying what he has photographed is a challenge. For this Brian has turned to communities of naturalists on the internet, notable at BugGuide (https://bugguide.net). With this help and his own field guides, Brian has identified the species of some 320 of his finds. Much of the pleasure he finds in the photographs are more aesthetic than academic, however. He will focus in on a part of an insect to admire the patterning: the vivid striping on the side of a swallowtail caterpillar feeding on his fennel, or the network of veins in a grasshopper’s wing. If sufficiently close-up, such a picture loses all sense of function, becoming an abstract piece of art.

I haven’t equipped myself with a macro lens yet, but merely knowing of Brian’s project has changed my attitude toward my garden. Stepping outdoors now feels like going on safari. I find a greater richness to my landscape as I contemplate all the diversity it supports. What I used to view as pests, I more often think of now as assets.

Thomas Christopher is the co-author of “Garden Revolution” (Timber Press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org

Be-a-Better-Gardener is a community service of Berkshire Botanical Garden, one of the nation’s oldest botanical gardens in Stockbridge, MA. Its mission to provide knowledge of gardening and the environment through 25 display gardens and a diverse range of classes informs and inspires thousands of students and visitors on horticultural topics every year. Thomas Christopher is the co-author of Garden Revolution (Timber press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org.