Know the Tricks to Get the Most Out of Your Annuals

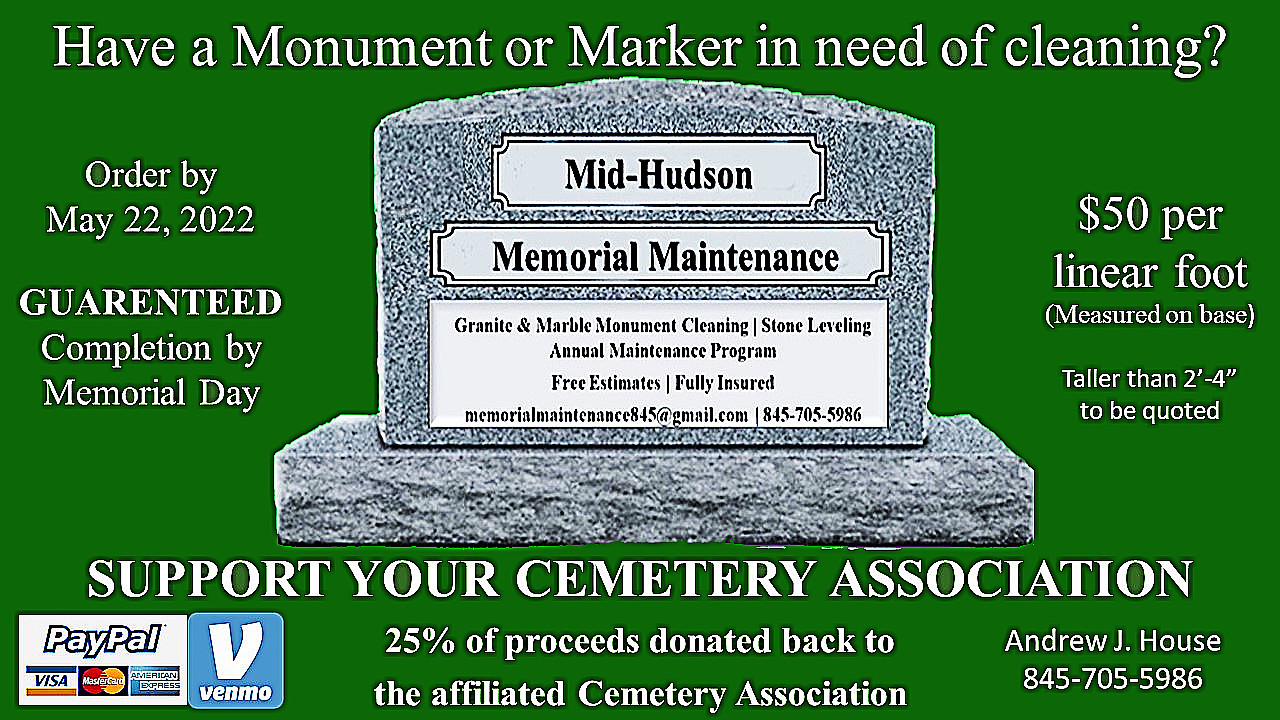

Annuals like Nicotinia provide quick gratification, going from seed to bloom in a matter of weeks.

By Thomas Christopher

I’ve always had a special love of annual flowers. This was true even back in the days when annuals were regarded as infra dig by fashionable gardeners. I love the quick gratification that annuals provide, going from seed to bloom in a matter of weeks. This encourages experimentation and risk-taking. A planting of perennials regularly takes three years to mature, and the plants themselves are quite expensive, so you tend to play it safe when designing with them.

Annuals, though, are relatively cheap, especially if you grow them from seed, and the wait to see the results of your planting is brief, so if you don’t like how a design turns out, you just root it out and replant with something else. I’ve tried out all sorts of off-beat color combinations with annuals, and gardens with various themes. One year I planted a horticultural nocturne around a little terrace. Four o’clocks (Mirabilis jalapa), white flowering tobacco (Nicotiana sylvestris) and moonflowers (Ipomoea alba) would all open as I arrived home at the end of the day, perfuming the evening air and drawing ghostly moths as their pollinators.

Another time I planted an entire backyard garden of curly cress (Lepidum sativum). I dug the soil in the beds, raked it smooth, and then dribbled lime between my fingers to create patterns of arabesques, curlicues, lightning bolts, and other garden graffiti. When I had finished the patterns to my own satisfaction, I planted everywhere there was lime with curly cress seeds, working them into the soil lightly with a hand cultivator. I watered daily to keep the seed moist and within days a green, free-form parterre began to appear. I timed my planting to peak on the evening that my wife had reserved for a barbecue with her colleagues, and when lit by spotlights, the garden was eccentric but stunning.

Plants that are such sprinters need a special kind of care. Perennials, the plants with which many of us started gardening, do best if grown lean, given just enough fertility and water to make compact, hardy plants. Annuals, by contrast, need a rich soil, and regular fertilization and irrigation. I like to dig in a couple of inches of compost and a dose of some balanced organic fertilizer when I am preparing the bed for planting. Then, if I am using transplants bought at the garden center, I pinch off any flower buds before inserting the plants into the soil and I water them with a soluble starter fertilizer, or a half-strength solution of some regular soluble fertilizer. I feed at planting time because greenhouse-grown plants are raised on a regimen of frequent fertilizations and will suffer if this treatment abruptly ceases.

After this, I watch the plants to monitor their growth. If it stalls, I may fertilize again with a water-soluble product; again, I typically apply it at half the strength recommended on the product label. I cut the fertilizer’s strength for two reasons. First, because the recommendations on fertilizer labels are typically on the generous side. After all, why wouldn’t the company want to sell more of its product? Second, because rather than deliver a big jolt of nutrients all at once, perhaps more than the plant can use, I prefer to give a more modest feed and then repeat a couple of weeks later if the first treatment doesn’t prove sufficient.

If I have saved any shredded leaves from my fall clean-up, I’ll use these to mulch the annuals; if not, I’ll scratch the soil surface between the plants to create a “dust mulch,” an old fashioned gardener’s expedient that doesn’t add organic matter to the soil but does help to insulate it, keeping the plants’ roots cooler and moister. “Deadheading” is a must; you must keep pinching off the flowers as they wilt to keep the annuals from setting seed if you want them to keep blooming.

Thomas Christopher is the co-author of “Garden Revolution” (Timber Press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org

Be-a-Better-Gardener is a community service of Berkshire Botanical Garden, one of the nation’s oldest botanical gardens in Stockbridge, MA. Its mission to provide knowledge of gardening and the environment through 25 display gardens and a diverse range of classes informs and inspires thousands of students and visitors on horticultural topics every year. Thomas Christopher is the co-author of Garden Revolution (Timber press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org.