Gardening in Mud Season

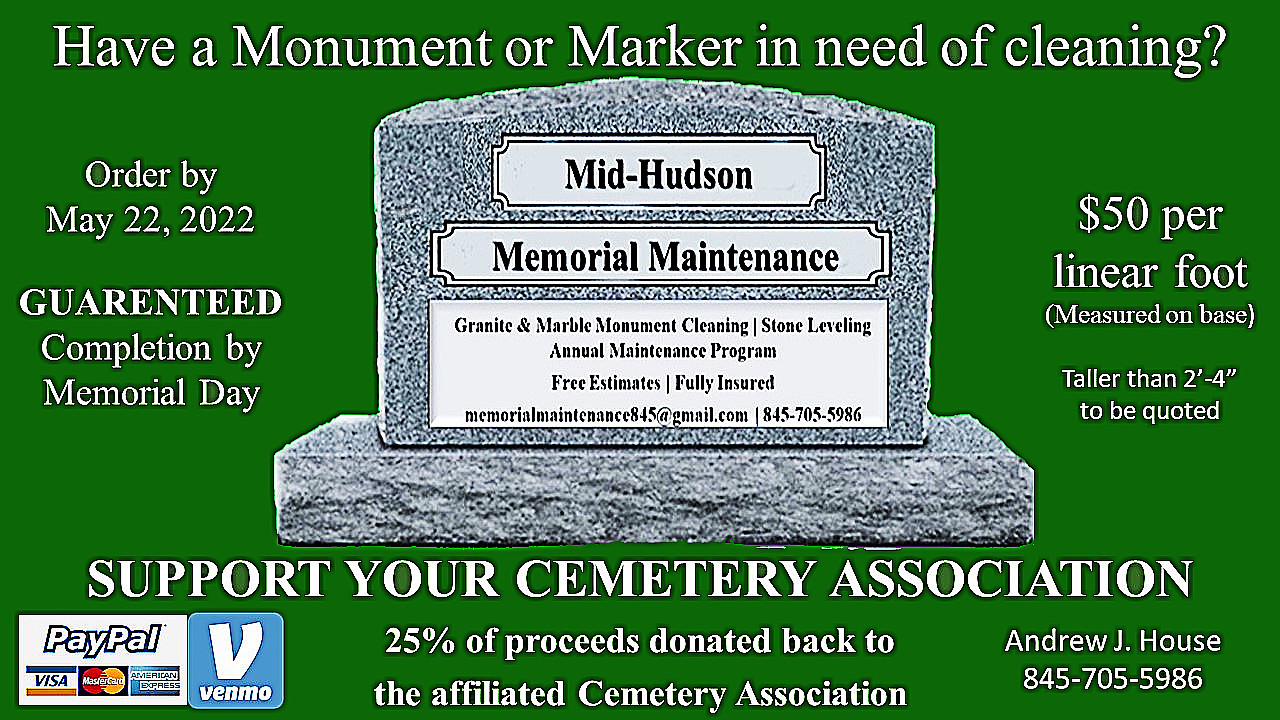

Raised vegetable beds at Berkshire Botanical Garden help dodge mud season and provide a jump start on planting.

By Thomas Christopher

Growing up in a New York City suburb, my first encounters with mud season were through the stories of my sister, who in her twenties moved to central Vermont. Most memorably, one day early during her first spring there, she pulled out of her driveway and onto her dirt road. Her car promptly sank to its axles. Indeed, it had sunk so deep into the mud that she couldn’t open her driver-side door. Instead, she had to climb out of the passenger side of the vehicle. Her travails were not over, however, for with her first step out of the car, she herself sank into her knee. She pulled free, but at the cost of a shoe which the mud sucked off her foot.

Since moving to a house at the end of a two-mile-long dirt road in a Berkshire hill town, I’ve collected a few mud season stories of my own. I try to drive as little as I can at that time of year, and I definitely don’t work in the garden. I don’t work in the garden then because the soil there right after it thaws is almost as sodden as the dirt in our roadbed. Working water-saturated soil with a spade or fork, or even just stepping on it, is likely to compress it. The pores in the soil collapse, decreasing the soil’s ability to absorb water and to drain and making it impenetrable to plant roots. In my younger, more ignorant, days I reduced some clay soils to something like concrete through such premature cultivation.

After decades of gardening in the North Country, however, I have developed a good sense of when the soil has dried enough to become workable. But if I am in any doubt, there’s a simple test. I scoop a trowel-full of earth out of a bed, squeeze it into a ball with my hand, and then poke it with a finger. If the soil ball breaks apart, the bed’s ready to dig. If the ball resists breaking and holds together, it’s still too wet.

Different soils dry at different rates. Coarser grained, sandy soils dry more quickly than finer particle silts or clays. Clays, such as the soil found in my garden and widely throughout our area, are especially prone to compaction. This is because their mineral particles carry an electrical charge and tend to bond to each other and to water molecules. This means that clays hold on longer to the water that seeps into them as the snow melts. Premature cultivation is especially fatal to them.

I would have no early spring crops, in fact, had I not created a series of raised beds at one end of my garden. I framed up six, 4ft. X 8ft. beds with lengths of 2in. X 8in. lumber. Then I filled these beds with a heavily amended mix, so that their contents are approximately equal parts of sand, compost, and soil. This blend is less water-retentive than the surrounding clay, and because these beds are raised up above the rest of the garden, they thaw a couple of weeks earlier and drain more quickly. It is in them, before the end of mud season, that I plant my first crops of spring greens: lettuce, arugula, and curly cress.

The same qualities that make these raised beds earlier to thaw and quicker to drain in spring make them more prone to drought in mid-summer. At that season, I often need to water them almost daily. If I provide sufficient irrigation, however, they are ideal for heat-loving crops such as bush beans, nasturtiums, and zinnias. I have even devoted a couple of these beds to plantings of perennial herbs such as sage, tarragon, and lavender. These plants thrive in the drier, quick-draining conditions, developing a superior flavor and fragrance.

Thomas Christopher is the co-author of “Garden Revolution” (Timber Press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org

Be-a-Better-Gardener is a community service of Berkshire Botanical Garden, one of the nation’s oldest botanical gardens in Stockbridge, MA. Its mission to provide knowledge of gardening and the environment through 25 display gardens and a diverse range of classes informs and inspires thousands of students and visitors on horticultural topics every year. Thomas Christopher is the co-author of Garden Revolution (Timber press, 2016) and is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden. berkshirebotanical.org.