PORTLAND, Ore. — At the Multnomah County Courthouse, it’s not uncommon for dozens of Portland-area residents to face eviction proceedings on any given Monday. Among them this week was Ahmeah Brown, a 21-year-old junior at Portland State University, who found herself navigating a legal process far more intimidating than the college track meets where she regularly shines.

Despite being a determined student-athlete and working two jobs, Brown arrived at court unsure of what to expect. Like many in her position, she mistakenly believed her “first appearance” was an eviction trial. “After this trial, I’m going to have to pack up,” she recalled thinking.

Brown is one of hundreds of Portland-area tenants facing eviction each month in what has become Oregon’s busiest eviction court. According to Portland State University’s Evicted in Oregon tracker, 800 to 1,100 people in Multnomah County are subject to eviction proceedings monthly — nearly half of all evictions statewide. A staggering 88% of those cases stem from nonpayment of rent.

A System Stacked Against Tenants

Only about 15% of tenants in eviction court have legal representation. Landlords, by contrast, often appear with attorneys or designated representatives. Unlike criminal court, tenants in eviction proceedings aren’t guaranteed legal counsel.

“This system is set up against most regular people,” said Kamron Graham, executive director of The Commons Law Center, a nonprofit offering free legal support to tenants facing eviction.

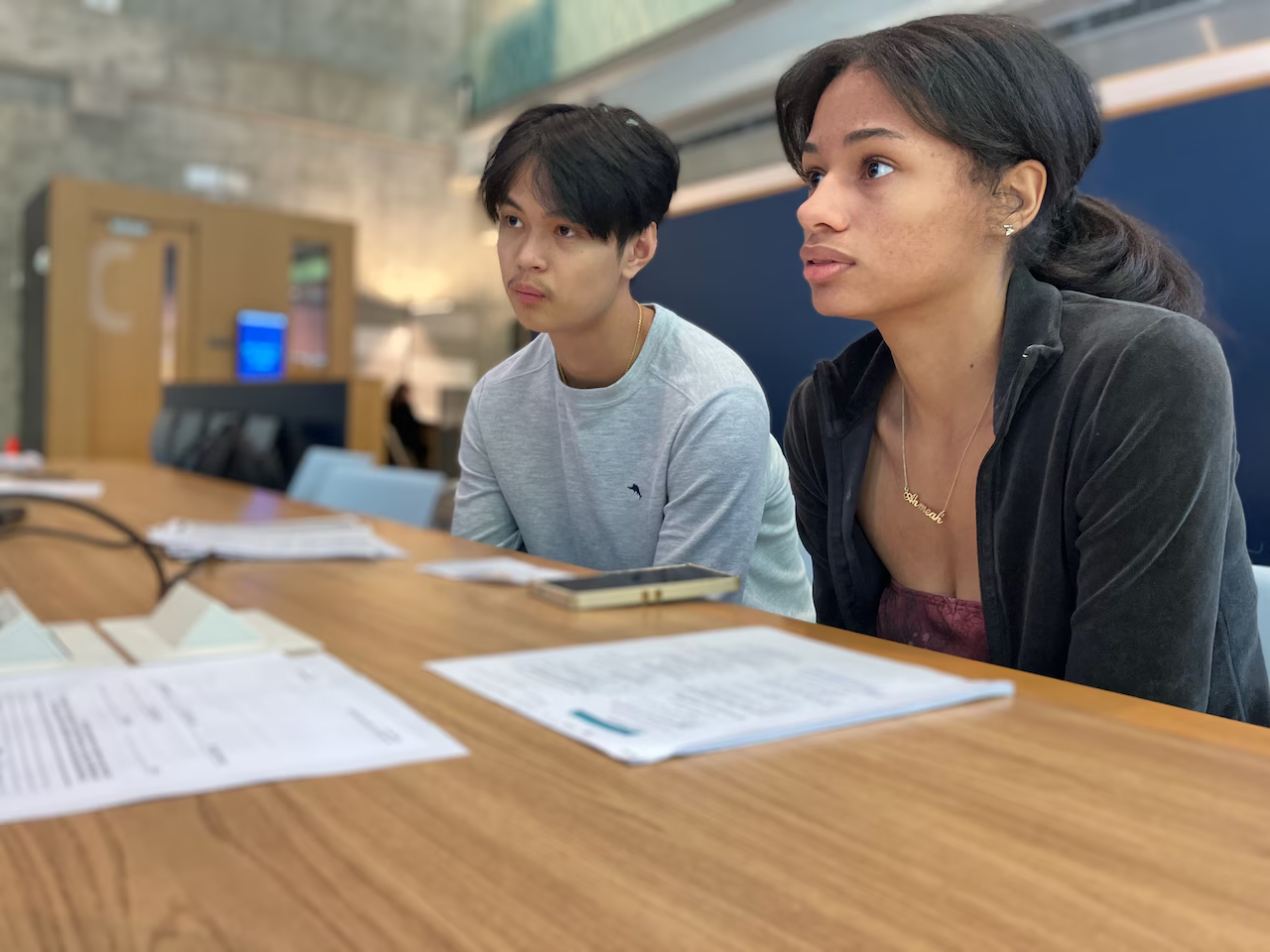

On Monday, Brown was quickly greeted by Xinyi Gu, a summer clerk with the Commons Law Center. Gu added her to the center’s list of clients for the day, giving Brown the kind of support she didn’t know she could hope for.

Inside the courthouse’s Crane Room, Graham’s team used bright sticky notes on desk partitions — like a restaurant’s order tickets — to organize tenants ready for negotiation or check-out. Of the 35 people on the docket, the law center assisted 13 tenants, including a few who asked for help after proceedings had already begun.

Budget Cuts and Rising Need

Despite the clear need, state and county budget cuts are threatening these legal aid services. Funding for the Commons Law Center’s eviction clinic is set to expire on December 31, and without replacement funds, Graham says the program may shut down.

Multnomah County trimmed $700,000 from eviction prevention programs, and the state reduced its total funding from $130 million to $44 million — just 25% of what Governor Tina Kotek had proposed.

“It’s very frustrating,” Graham said. “We’re trying to prevent people from becoming homeless, and this is how it happens.”

The Human Toll

Brown’s journey into eviction court reflects the stories of many tenants caught in financial hardship. After escaping homelessness as a teen in Eugene, Brown juggled school, running, and two jobs at the Moda Center and mentoring youth. Still, she fell behind on rent and couldn’t bring herself to ask for help.

“I felt like I could do it myself,” she said. “And I was embarrassed.”

She had no close family in the area and feared that an eviction on her record would make it impossible to find future housing.

With the help of Commons Law attorney Julia Winett, Brown learned she owed $1,988 in back rent and fees. She’d already scraped together $700 by asking friends for help and believed she could raise the rest soon. “I feel a lot better,” she said tearfully. “I thought I was going to an eviction trial.”

Winett helped Brown understand that first appearance days are primarily meant to reach settlements — not to issue eviction orders. “The only person who can evict you is a judge,” Winett told her. “The only person who can remove you is a sheriff.”

Not Just a Legal Problem — A Housing Crisis

The broader housing crisis in Portland has intensified the demand for assistance. Last year, over 18,800 people received eviction prevention support in Multnomah County, with 92% still housed a year later. Yet, as state and county leaders reduce funding, thousands more like Brown may go unprotected.

One Commons Law client, Mo, a single mom of two boys, was saved from a full eviction bill by Winett’s negotiations. Mo, who had struggled with delayed rental aid through Oregon Health Plan, said the help was “incredible.” But like many, she still didn’t know where she and her children would live next.

“It takes so much more energy to survive than it ever has,” she said.

A Temporary Victory

Brown’s case isn’t over. Her eviction trial is scheduled for September 11, giving her time to seek further rent assistance and hopefully stay in her apartment. But her story illustrates a much larger reality: Without timely support, many Portlanders risk slipping into homelessness — even those who are working, studying, and doing everything right.

And with legal aid programs hanging in the balance, the future remains uncertain.

“It’s about keeping people housed,” said Graham. “That’s why we’re here.”

Leave a Reply