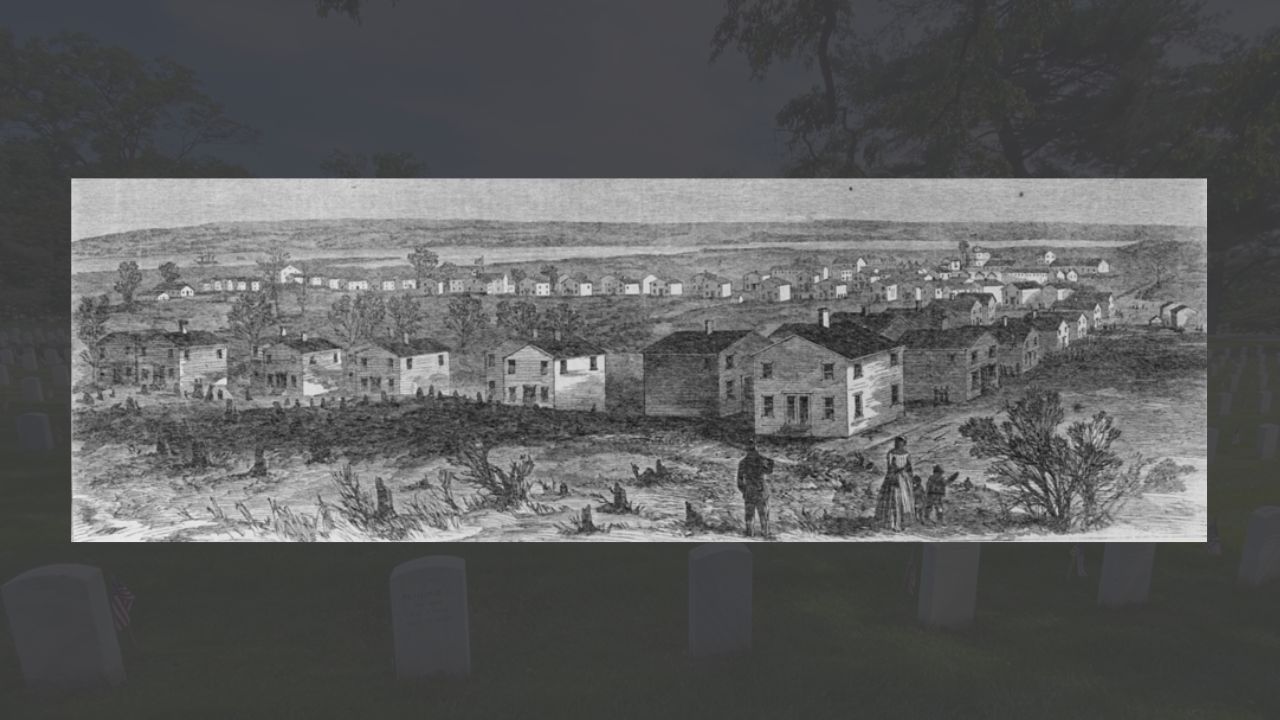

In the shadow of Arlington National Cemetery once stood Freedman’s Village, a remarkable and often-overlooked community established in 1863 for newly emancipated African Americans. Built on land seized from Confederate General Robert E. Lee, this village symbolized freedom, resilience, and a new beginning for hundreds of formerly enslaved people during and after the Civil War.

From Contraband Camps to a Model Settlement

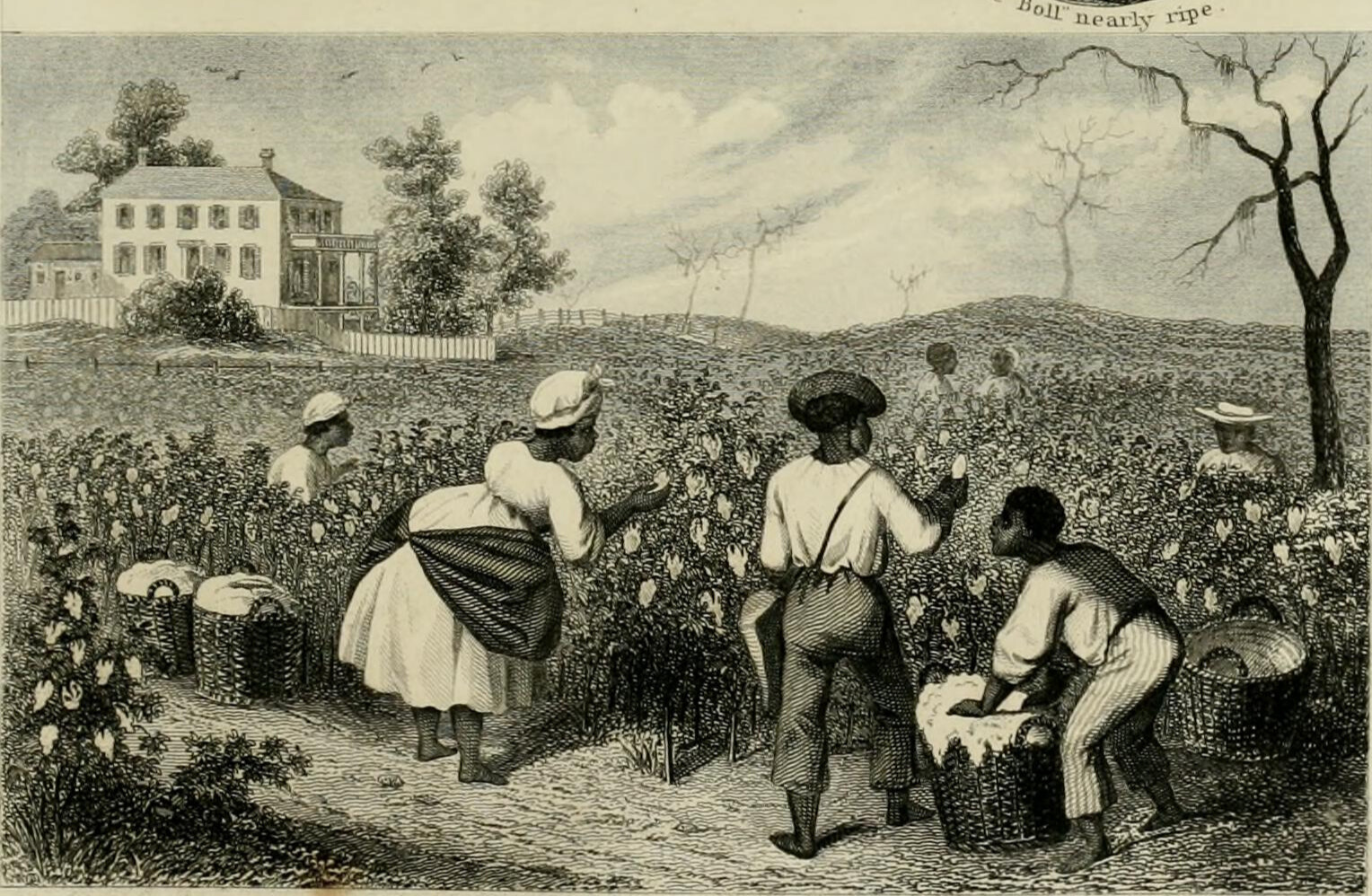

Following President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the earlier abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C. in 1862, thousands of enslaved individuals fled to the capital in search of safety. Overcrowded contraband camps, a term used by Union forces to describe escaped slaves treated as confiscated enemy property, quickly became breeding grounds for disease and hardship.

To address this crisis, Lieutenant Colonel Elias Greene and Danforth Nichols proposed establishing a new settlement on Arlington Estate, the former home of Robert E. Lee. The choice of location was symbolic—turning the land of the Confederacy’s most iconic general into a refuge for the people he had once fought to keep enslaved.

On December 4, 1863, Freedman’s Village officially opened with a ceremony attended by members of Congress.

A Village Designed for Dignity and Opportunity

The village featured over 50 wooden houses, each one-and-a-half stories tall and divided to house two families. Planners laid out streets and parks, naming them after Union leaders. Maps from 1865 show designated areas for public services, transforming the village into a proper town rather than a temporary shelter.

Though it was initially built for around 600 residents, word of its better living conditions spread quickly, and the population swelled to over 1,100 people.

Education as a Cornerstone of Freedom

Education was at the heart of Freedman’s Village. The first school opened on December 7, 1863, with 150 students. By the next year, that number grew to 900, including both children and adults.

Run by the American Tract Society from Boston, the schools offered reading, writing, and basic life skills. By 1865, the village also had a secondary school, giving Black Americans access to educational opportunities that had once been forbidden under slavery.

Vocational Training and Employment

The government required all able-bodied adults in the village to work. Vocational schools taught men trades such as blacksmithing, carpentry, and wheelwrighting, while women learned sewing and domestic skills.

Residents produced goods for their own community, like desks for classrooms and clothing for the elderly. Meanwhile, others worked on nearby farms growing wheat, corn, and vegetables, helping the village achieve a level of self-sufficiency and economic activity.

Health Services and Social Support

In November 1866, the village opened Abbott Hospital with 50 beds and 14 staff. Despite limited resources, the hospital provided essential care and significantly reduced mortality compared to D.C.’s crowded camps.

A home for the elderly and disabled was also established, offering shelter to those unable to work. Public health workers visited homes regularly to monitor illnesses, particularly during outbreaks of measles, scarlet fever, and whooping cough.

Sojourner Truth’s Powerful Influence

In 1864, famed abolitionist Sojourner Truth moved to Freedman’s Village as a representative of the National Freedman’s Relief Association. She helped villagers find work, taught women life skills, and educated them on their new rights as citizens.

When Maryland men attempted to kidnap children to re-enslave them, Truth intervened fiercely:

“If you try that again, I will make the United States rock like a cradle.”

Her activism during this time cemented her legacy and even led to her meeting President Abraham Lincoln—the first Black woman to do so at the White House.

A Thriving Community, Not Just a Camp

Although initially intended as temporary housing, Freedman’s Village became a thriving, self-sustaining community. Residents built churches, opened stores, and formed mutual aid organizations like the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, which offered burial services and financial assistance.

Many found jobs in federal offices, thanks to new anti-discrimination hiring policies, marking the village as one of the first communities where many experienced the true fruits of freedom.

Controversies Over Control and Taxation

Despite the promise of freedom, residents paid steep costs. Workers earning $10 per month on government farms saw half their wages taken as a “contraband tax” to fund the village’s upkeep.

These forced contributions sparked protests. Residents questioned why they were being taxed on land taken from former slaveholders when they had once worked without pay. Over the years, village control shifted between the Army, the Treasury, and eventually the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865.

The Fight to Save Freedman’s Village

By the 1880s, pressure to close the village mounted. Arlington Cemetery’s superintendent accused villagers of stealing firewood, and real estate developers eyed the land as Washington grew. Racism also played a role; some white neighbors opposed a large Black community with voting rights nearby.

On December 7, 1887, the government issued 90-day eviction notices, calling long-time residents “squatters” despite many having official permissions and even buying their homes.

John Syphax’s Legal Battle

John Syphax, born to a formerly enslaved mother at Arlington, became the voice of the village. He lobbied the War Department to compensate residents, requesting $350 per homeowner for property improvements.

His efforts delayed the demolition but couldn’t prevent it. Congress finally approved $75,000 in compensation in 1900, far less than what had been lost. The money went to surviving families, but for most, it came too late.

Today’s Remembrance

Freedman’s Village no longer exists, but its legacy remains within Arlington National Cemetery and Pentagon grounds. Visitors can find a historic marker at South Oak Street and Southgate Road.

At Arlington House, a scale model of the village is on display, offering a detailed glimpse into what once stood on that land. Section 27 of the cemetery holds graves of many original residents.

Admission is free, and visitors can explore these memorials daily from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Freedman’s Village was more than a refuge—it was a community of resilience, growth, and hope, built by people who had known only bondage and still dared to dream of a better life. Its story, long overshadowed, now takes its rightful place in American memory.

Leave a Reply