Washington, D.C., stands apart from most major American cities with its notably low skyline. Unlike the soaring towers of New York City or Chicago, the nation’s capital appears intentionally flat, punctuated only by its most iconic monuments: the Washington Monument and the dome of the U.S. Capitol. This unique cityscape is no accident of geography or short-lived building booms; it is the direct result of a century-old law known as the Height of Buildings Act.

Early Tall Building Concerns

In the late 19th century, rapid urban development began to stretch the boundaries of what Washington, D.C., could accommodate. In 1894, The Cairo—a luxury apartment building rising 164 feet on Connecticut Avenue—became the city’s tallest structure. Residents expressed alarm not only at its scale but also at safety issues: firefighting technology of the era struggled to reach its upper stories, and some worried the building’s foundations might not support its height.

Public unease over The Cairo spurred congressional action. Lawmakers debated how high downtown structures should be allowed to rise, weighing the benefits of density against concerns for public safety and the capital’s aesthetic character. Within five years, those debates yielded legislative change.

The 1899 Height Act

In 1899, Congress passed the original Height of Buildings Act. Its key provision was deceptively simple: no building could exceed the height of the U.S. Capitol, measured at 288 feet. The logic echoed early regulations adopted in other American cities—intended to maintain fire safety, ensure adequate light and air at street level, and avoid overwhelming the existing urban fabric.

However, by 1910 it became clear that the Capitol-based standard was too permissive for the relatively compact federal city. Urban planners and local advocates argued that a lower ceiling would better preserve views, reduce congestion, and reinforce Washington’s distinctive character.

The 1910 Amendment and Modern Restrictions

Responding to those concerns, Congress amended the Height Act in 1910 with far stricter limits. The new framework tied allowable building height to the width of the adjacent street:

-

Commercial corridors: Maximum height of 130 feet

-

Residential streets: Maximum height of 90 feet

-

Pennsylvania Avenue (selected sections): Up to 160 feet

Under this rule, a building on a 100-foot-wide commercial street could rise no higher than 100 feet. The intent was to harmonize massing and scale across neighborhoods, while also protecting sightlines to the Capitol, the Washington Monument, and other federal landmarks. These height provisions remain in force today, effectively capping vertical development across most of the District.

Arguments for Preservation

Supporters of the Height Act often invoke the city’s founding visions. Thomas Jefferson, alongside Pierre L’Enfant—the capital’s original designer—envisioned a low, spread-out city reminiscent of Paris, with grand boulevards and unobstructed vistas. Marcel Acosta, executive director of the National Capital Planning Commission, has pointed out that “our forefathers planned a city that emphasizes views to and from important public places.” The result is a pedestrian-friendly, sunlit urban environment that many residents and visitors cherish.

Maintaining a uniform skyline also reinforces Washington’s symbolic role. Unlike commercial hubs defined by glass-and-steel icons, the capital’s built environment highlights democracy’s enduring institutions rather than private enterprise. The relative restraint in height directs focus toward civic architecture and ceremonial spaces rather than corporate logos.

Debates and Calls for Change

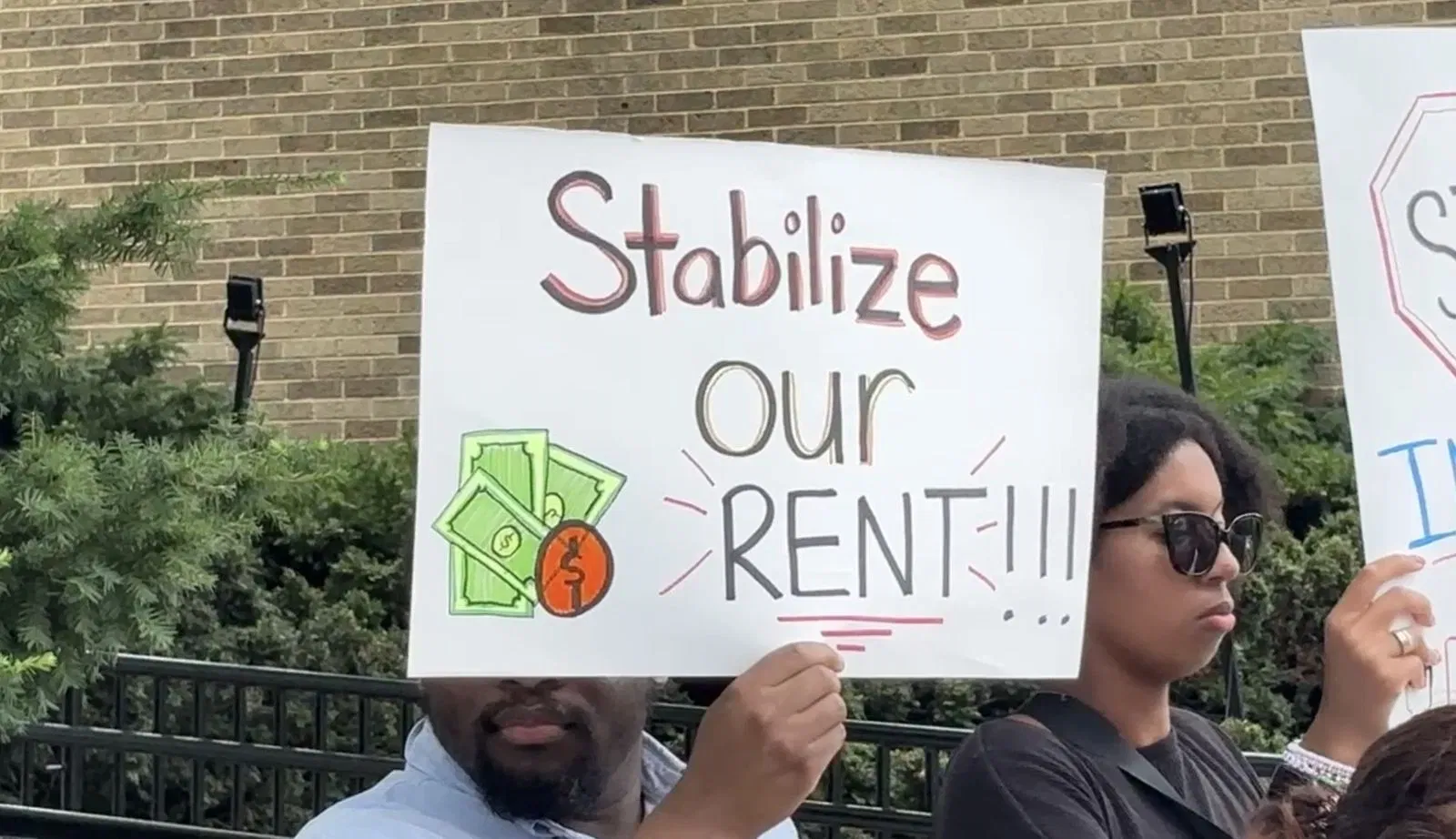

Despite these advantages, critics argue that the Height Act has unintended social and economic consequences. Washington’s land area is fixed, and its population and housing demand continue to grow. With no room to expand vertically, developers build outward—or not at all—pushing housing costs upward and encouraging suburban sprawl. “We’re running out of land,” warns land-use strategist Chris Leinberger. “At some point, we have to decide whether to go up or out.”

In 2012, former D.C. Planning Director Harriett Tregoning proposed a modest revision: selectively raising height limits in certain high-density areas while preserving core viewsheds. The plan would have allowed slightly taller buildings—enough to ease housing shortages—without threatening the monuments’ prominence. However, the D.C. Council swiftly rejected the proposal amid concerns that any relaxation would set a precedent for uncontrolled development.

Balancing Growth and Heritage

As Washington navigates future growth, planners and policymakers face a delicate balancing act. On one hand, maintaining the city’s commemorative character and open public spaces remains paramount. On the other, the urban pressures of the 21st century—rising rents, longer commutes, and environmental sustainability—demand creative solutions.

Some experts advocate for targeted height increases along key transit corridors, coupling development with new parkland and infrastructure improvements. Others call for a comprehensive review of the Height Act to introduce flexibility while codifying protections for major sightlines. Crucially, any change would require coordination among Congress, the D.C. government, and federal planning bodies.

Conclusion

Over a century after its enactment, the Height of Buildings Act continues to shape Washington’s skyline, reinforcing a cityscape defined by monumental horizontality rather than vertical ambition. While the law protects cherished views and underscores the capital’s symbolic role, it also constrains housing supply and economic density. As the region evolves, the debate over building heights in Washington, D.C., will inevitably resurface—forcing a reevaluation of when and how a modern capital can rise without losing the vistas that make it unique.

Leave a Reply